Time to put down the matches: why we need to end the burning of EnglandтАЩs uplands

The decisions made by this government on the burning of upland heath in the coming months will have a huge bearing on the UKтАЩs ability to meet climate goals, restore biodiversity and deliver on our promise to protect 30% of land for nature by 2030. ║┌┴╧╒¤─▄┴┐тАЩs Oliver Newham argues that whatтАЩs needed now is the political courage to deliver.

Published 25/06/2025

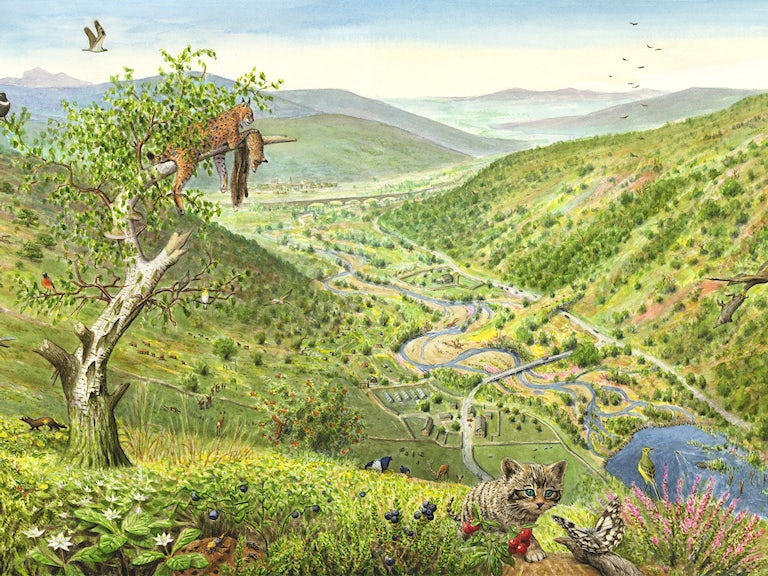

At ║┌┴╧╒¤─▄┴┐, we demand bold action for nature. That means supporting ecosystems to recover and re-establish their natural functions, free from destructive land management practices that have brought us to the brink of ecological and climate breakdown. One of the worst offences has been burning on peat in EnglandтАЩs uplands, often in support of driven grouse shooting тАУ with grouse preferring to feed on young shoots of heather.

The UK Government recently published backed up with an and тАУ to which we submitted a consultation response. ItтАЩs a long-overdue move, significantly expanding the areas to be protected from further burning. Indeed, if implemented, these changes will increase the area of uplands currently protected from 222,000 hectares to over 368,000 hectares. In short, all of EnglandтАЩs deep peat would be protected and have a chance to start to recover.

Why does peat matter

Quite simply, because peatlands have superpowers. Far from being humble тАЛтАШbogsтАЩ, they lock away carbon, clean our water, reduce flood risk, and support specialist wildlife that cannot live elsewhere. But right now, the vast majority (80%) of these ecosystems in England are degraded and burning is a big part of the problem. [1]

LetтАЩs be clear: burning peatlands is indefensible.

The science leaves no room for doubt. [2] Natural EnglandтАЩs own evidence gathering shows that repeated burning degrades the very fabric of peat soils, reduces biodiversity and releases massive quantities of stored carbon, sometimes up to 80% of above-ground carbon stock.[3] This is also not about eroding history; driven grouse moorland management has taken place in Britain for less than 200 years, replacing a far longer history of wetter and wilder moors.[4]

So we welcome the proposed expansion of protections from burning to cover all upland deep peat within Less Favoured Areas тАУ ie those areas in the English uplands identified by the UK Government as challenging for farming, including profitability. We would also encourage the government to consider extending the ban to include peat less than 30cm deep. In Scotland, recent legislation on muirburn didnтАЩt go far enoughтАЙтАФтАЙand still allows burning at 40cm.

In short, all upland peat soils deserve safeguarding, with shallower peatlands and ecologically important habitats such as wet heath all deserving increased protection. Indeed, many areas which are currently under 30cm depth were once deeper, but have been eroded, drained or burnt.

If weтАЩre serious about our climate and nature targets there is also a further challenging issue to be considered: much of our lowland peat is not protected from damage despite strong evidence of the potential climate-related benefits of doing so.[5] The solution is likely complex and needing detailed conversations and consideration.

In acknowledging and welcoming these proposed changes, we must remember that this will not be achieved via new regulation alone. ItтАЩs also essential that enforcement against illegal burns is strengthened. So far this has been woefully lacking and existing regulations are widely abused.[6] To date, burning has continued on protected sites at similar, or even higher, rates than on non-designated land; a damning indictment of failed enforcement approaches by governments past and present.

Peatlands, our unsung heroes

Peatland is formed by an accumulation of mosses and other plants, and is one of the greatest stores of carbon in the landscape. Globally, peatlands store more carbon than the worldтАЩs rainforests. Peatland goes on drawing down carbon over centuries and millennia as layers of peat accumulate.

The UK has about 13% of the worldтАЩs blanket peat bog, classified by the International Union for Conservation of Nature as one of the worldтАЩs rarest habitats. These peatlands represent the single most important terrestrial carbon store in the UK [7] тАУ and yet they are in trouble, because of drainage, extraction, overgrazing and burning.

A pathway for peat

If new legislation is to be successful in protecting peat and allowing it to recover, hereтАЩs what it will take:

- Stronger dissuasive penalties, including large fines and speedy prosecutions that actually deter illegal burning.

- More boots on the ground. Natural England needs more funding to monitor and enforce.

- A legally binding and enforced Management Code to replace the toothless voluntary guidelines (Defra has promised they will soon publish an updated Code which will be mandatoryтАЙтАФтАЙa welcome move)

- More support for the land managers responsible for restoring our nationтАЩs peatlands, including funding and specialist advice.

- Training for anyone seeking a burning licence. This should include training on the ecological consequences of burning and the benefits of alternative, non-destructive management methods.

WeтАЩve also identified loopholes in the proposals, which must be addressed.

- The current exemption that allows burning because a site is тАЛтАЬinaccessible to machineryтАЭ must go. The idea that nature must be burnt just because itтАЩs hard to reach belongs in the 19th century. We need to support resilience and that means natural grazing, rewetting and giving landscapes space to recover, not the setting of more fires.

- Controlled burning for firebreaks should only ever be a last resort, not a default tool. We do recognise the need to manage wildfire risk, which is clearly increasing with our hotter, drier summers [8] тАУ but the solution must be smart, not destructive. That means embracing completely different approaches such as rewetting peatlands, which has been proven as an effective way to prevent fires, by restoring natural resilience to the land.[9] When firebreaks are needed, mechanical cutting should be the go-to method.

- The proposal to remove protection from Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs) outside Less Favoured Areas (LFAs) must be treated with caution. While SSSIs donтАЩt always align well with delivering rewilding and dynamic outcomes at scale, the use of LFAs as qualifying criteria should be in addition to тАУnot in place of тАУexisting protections.

- We also must put a stop to any idea that тАЛтАШresearchтАЩ is a legitimate reason to keep burning on peat. ThereтАЩs already enough research to fill a library, almost all of it saying the same thing: burning peat is bad for biodiversity, carbon, water and public health.[10] If the UK Government really does insist on a research exemption, it must only be done in wholly exceptional circumstances, with cast-iron safeguards to prevent abuse.

For peatтАЩs sake

This really is a moment of truth. The decisions made post this consultation will shape the future of EnglandтАЩs uplands and, by extension, our nationтАЩs ability to meet climate goals, restore biodiversity and deliver on our promise to protect 30% of land for nature by 2030.

We know what we need to do: we must end routine burning on upland peatlands and shift to principles that regenerate rather than deplete, including an urgent shift to natural process-led land management in much of England. That means backing rewilding and nature-led recovery at scale. It means long-term funding that enables people to choose to restore nature at scale and make nature their business.

We know it can be done. WhatтАЩs needed now is the political courage to deliver. Act for the interest of all, not the few.

Peatland restoration in action

Through our Rewilding Innovation Fund weтАЩre supporting a peatland restoration project in ScotlandтАЩs largest regional park. The Yearn Stane project is using drone surveys and a 4k camera to survey over 5,000ha of peatland to aid restoration, provide data and capture footage for public engagement activities.

Stand up for nature

Thank you for acting wild.

Join the movement

Keep up to date with ║┌┴╧╒¤─▄┴┐тАЩs campaigns for change by joining our mailing list.

Sign up to our newsletterPush for change

Urge your local leaders to act wild and commit to supporting the Rewilding Manifesto.

Bain, C. et al, (2011) , IUCN UK Peatland Programme, Edinburgh. p10 and p38

Ramchunder, S. J., Brown, L. E., & Holden, J., (2009) . Progress in Physical Geography: Earth and Environment, 33(1), 49-79. (Original work published 2009)

Noble, Alice Kathryn, (2018) . PhD thesis, University of Leeds.

Davies, G. M., Gray, A., Power, S. C. & Domenech, R., (2023)

- Natural England, (2025)

- Fieldsports Journal, (2020)

- Green Alliance, (2023)

Emily Beament, (2022), The Standard

RSPB, (2022)

- Bain, C. et al, (2011) , IUCN UK Peatland Programme, Edinburgh. p10 and p38

- Baker, S J et al, (2025) тАШ.тАЩ Environmental Research Letters

- IUCN, (2024) , IUCN UK Peatland Programme

A M Graham et al, (2020) , Environmental Research Letters

Rei Tavker, (2023) , Sheffield Wire